61- WHAT DOES JESUS SAVE US FROM?

What does jesus christ save us from? jesus himself explains it

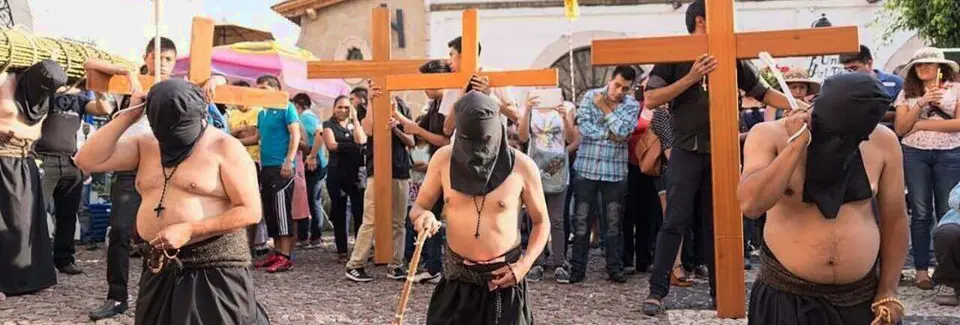

!(center)https://radialistas.net/wp-content/uploads/media/uploads/fotos_series/otro-dios/61g.jpg(alt_text)!

RACHEL Yes, hurry it up, give me space. Do we have a signal now? Are we on the air? … Good morning, Jesus Christ.

JESUS [Yawning] Good morning, Rachel. Why are you so anxious?

RACHEL I’m anxious and you’re still half asleep.

JESUS What happened is I spent the night talking with a family from here in Nazareth. They told me how difficult life is for them nowadays.

RACHEL Well, get wide awake, because your last comments about original sin have aroused some extremely strong reactions. From all the questions we’ve received, I pick out this one If there was no original sin, then why did you come into the world?

JESUS Well, I came into the world … because my mother brought me into it! Surely that’s the case also with our friend who asked the question.

RACHEL But he’s surely referring to redemption.

JESUS To what redemption?

RACHEL You are the Redeemer of the world, the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world.

JESUS I’m a lamb, really? Listen, Rachel, there was a time when people thought that God, up there in heaven, got angry and vexed with us for what we were doing on earth. They thought he sent lightning bolts and floods, destroyed towers, and punished us with fire and brimstone. We thought we had to do something to calm God’s anger.

RACHEL And how could it be calmed?

JESUS They say that some peoples went so far as to sacrifice human beings. Even our father Abraham thought that he had to sacrifice his son Isaac, but just as he was ready to thrust the knife into the boy, God stopped him.

RACHEL I imagine God is repulsed by human sacrifices.

JESUS He detests them. Later on, people thought that they could placate God’s wrath by sacrificing animals, such as sheep, goats, doves. The temple of Jerusalem was a slaughterhouse; there was blood gushing out on every side.

RACHEL And was God pleased with that?

JESUS How could he be pleased with that? Tell me, Rachel, do you have a pet animal in your house?

RACHEL In my house? Well, my kids have a dog. They call him Mocho.

JESUS And if one day you got upset with your kids, would you be pacified by having them kill Mocho for you or perhaps slaughter the neighbor’s cat?

RACHEL Gosh, don’t talk like that.

JESUS Luckily, the prophets did talk like that. Hosea said God does not want sacrifices, but mercy. Isaiah said The sacrifice that is pleasing to God is breaking the yoke of injustice, sharing your bread, helping the orphan and the widow. God doesn’t need blood, Rachel. God doesn’t want blood.

RACHEL Not even your blood?

JESUS My blood?

RACHEL They’ve always taught us that your sacrifice on the cross was pleasing to God.

JESUS What you’ve just said really offends God. How is God going to be happy about innocent blood being shed? God is my father. He is also your father. How can a father want his little ones to be killed? How can he be thirsting for blood in order to calm his wrath? Such a God would be a monster worse than that Moloch who devoured his own children.

RACHEL Well, now let’s see what our audience has to say … Hello?… Yes?

WOMAN Look, I am very confused about everything I hear on your program. I only want Jesus to clear up one thing for me. Did he come to save us? Yes or no?

RACHEL How do you answer that, Jesus?

JESUS Well, of course I did. I spoke about salvation. I preached salvation.

WOMAN Salvation from sin, … from our sins?

JESUS No, not from sin, because each person will give an account to God for what he or she has done, for the harm they have done to others, for the harm they have done to themselves….

WOMAN So what do you come to save us from?

JESUS From believing in a bloodthirsty God. In all truth I tell you God is love. And only love saves us.

RACHEL Did you hear that, my friend? Do you have another question? Can you hear me, dear? … I don’t know if she hung up the phone or was just left speechless. Well, we have to take a commercial break now, and in a few minutes we’ll continue with another burning topic, which will be a great surprise for those of you listening to us. From Nazareth this is Rachel Perez, reporting for Emisoras Latinas.

MUSIC

ANNOUNCER Another God is Possible. Exclusive interviews with Jesus Christ in his second coming to Earth. A production of María and José Ignacio López Vigil, with the support of the Syd Forum and Christian Aid.

*More information about this polemical topic…*

Being saved among ourselves

The great Christian myth is the story of paradise: it is the story of a humanity separated from God and therefore evil, sinful, needing “salvation” in order to overcome that primeval rupture. The myth of paradise lost is complemented by the myth of paradise recovered, thanks to the salvation that Jesus offers us through his suffering and dying for us to pay off the original debt. But is all this mythology truly Christian? Is it based on the life and teachings of Jesus? What Jesus always taught and proposed, by his words and his actions, was the need to be saved among ourselves, by doing justice, practicing an efficacious love, and saving one another from sickness, marginalization, exclusion, shameful poverty, fear of an angry God …

The sacrificed lamb

Jesus was killed during the days of Passover, which was one of the Jewish people’s traditional feasts. The heart of the Passover celebration was a supper where families came together and ate a lamb that had been sacrificed in the Temple of Jerusalem. The image of the Messiah as the “lamb of God” had its origin in prophetic texts such as Isaiah 53,7. That same image is developed in John’s gospel, and it fascinated Paul, who was an obstinate proponent of a sacrificial theology (1 Corinthians 5,7). The author of the Apocalypse also makes abundant use of the symbol of the lamb.

The early Christian communities were persecuted to the point of shedding their blood in professing their faith. In their art, Jesus was often represented as a lamb that had been slaughtered or wounded in its side, but wearing a halo on its head. The image is still central to the eucharistic rite: Lamb of God, you take away the sin of the world…

A theology drenched in blood

Most New Testament authors, and especially Paul, were heirs to the Jewish culture, in which God was placated and honored by the shedding of the blood of lambs and other sacrificed animals. They were also surrounded by the empire’s pagan cults, in which animals were sacrificed to please the gods. They therefore understood the death of Jesus in terms of sacrifice: his blood redeemed humanity.

Right up to the present day that same sacrificial theology has great influence in traditional Christianity. It is expressed in Christian beliefs, devotions, and preaching, as well as in evangelical services and the liturgy of the Catholic mass. From every theological angle we are relentlessly reminded that Jesus’ blood “was shed for us”; it is what “saved” us.

Nothing in the life of Jesus indicates that he felt himself to be a “lamb of God” carried to the slaughterhouse by the divine will. What is characteristic and original in the message of Jesus is his proclamation of the Kingdom of God and his joyous confidence that things will change on earth, that justice will reign, that there will no longer be blood or sweat or tears shed unjustly. In the parable of the vineyard and the vine-growers (Matthew 21,33-46), God does not send his son so that they will kill him, but so that the rebellious vine-growers will mend their ways.

As little appreciation as Jesus evidently had for bloody sacrifices, Christianity very soon betrayed him. Feminist theologian Ivone Gebara explains it thus: The blood-drenched cross, which must have created in Christians an intense opposition to all unjust violence, also generated the false idea that suffering and sacrifice are necessary in order to draw close to God and be saved.

Traditional theology, bathed in sacrificial blood, is not Christian, although it has pretended to be such for countless centuries and still pretends to be so.

There should never be blood

Jesus reminds Rachel of how the patriarch Abraham was on the verge of sacrificing his son Isaac. Marc-Alain Ouaknin, a rabbi who has developed a very original way of interpreting the scriptures,

agrees with Jesus, that it was necessary for God to “stop” Abraham. He states: The meaning of that “stopping” is clear: You shall not act as do all those around you. In the name of God, the supreme value, you are not going to sacrifice either your son or any other human being. The “revolution” of Abraham consists in introducing respect for the other, even if this is “against” the word of God. What is revolutionary in this story is that the sacrifice of Isaac was not carried out. If this message is well understood, it means: there should never be blood and violence among human beings because of God.

How to escape from this theology

The theology of salvation by sacrifice that has its origins principally in the writings of Paul is a consequence of a “dualistic” mentality. Such theology consists in thinking that the world is a “vale of tears”, that we humans are evil sinners who were born in sin, and that we therefore need “to be saved” from the world and from our sins.

This dualism is very present in the Bible and in the Aristotelian thinking which had much influence on Christian theology. Such a dualistic vision affects all our knowledge and creates an abyss between God and the world. And in order to cross that abyss, people are desperately in need of sacrifices, offerings, mediators, sacred places, sacred rites, sacred moments, and, most definitely, a Savior. In this dualistic perspective, God reigns above everything, but does not dwell in anything. He is the Creator but does not reside in his Creation.

How are we to escape from this dualism? For Willigis Jäger, a Benedictine monk and Zen Buddhist master, we can escape by abandoning institutionalized religion and promoting true spirituality. He states: Acrobatic skating and hang gliding have much of the same religiosity that there is in a divine cult. Our body is more intimate to our essential nature than is our reason. The body encompasses a religiosity which is lacking in our ecclesial religious culture. We Christians have forgotten the spiritual energy of the body. I repeat often a statement that expresses the basis of the spirituality I try to transmit: Religion is our life, and the process of life is our true religion. God does not want to be adored; he wants to be lived.

Jäger recognizes, however, that religiosity has different levels, and humanity will remain for a long time at a religious level where salvation can be imagined only in terms of being redeemed by a redeemer.

Savior of whom? from what?

The feminist theologian Ivone Gebara reflects boldly on the “salvation” worked by Jesus when she states: For the Christian community Jesus is the symbol of its dreams, the symbol of what it most intensely desires for humankind and for the earth. These aspirations are modified by the community of Jesus’ followers in different contexts and at different moments of human history. Consequently, it might be said that Jesus is not the savior of all humanity in the traditional, triumphalist sense that has characterized Christian churches. He is not the powerful Son of God who dies on the cross and is transformed into the King who morally dominates the different cultures. He is simply the symbol of the fragile fraternity and the justice that we are seeking. …

He does not come to us because of a “higher will” that sent him. He comes from down here, from this earth, from this body, from the evolution of the past and of today. … As an individual person, Jesus is not superior to any other human being. He is from the same earth, from the same corporeal reality of which we all are made. However, given his moral qualities, given his sensitivity and his openness to others, he succeeded in somehow representing the perfection of our dreams, the ideal realization of our desires. The difference is not metaphysical or ontological; it is ethical and esthetic, because it is located in the human quality of his being, in the beauty of the attitudes that he was able to let flow from himself and from others. Jesus does not save us by being himself the foundation of hierarchical power, but by being the foundation of a new model of fraternal and sororal power, which inspires all of us who profess that we belong to his tradition.