76- A SAINT-MAKING FACTORY?

“how much does it cost to make a saint?”

jesus christ asks.

a powerful Catholic sect.

He was canonized very rapidly by the Vatican.

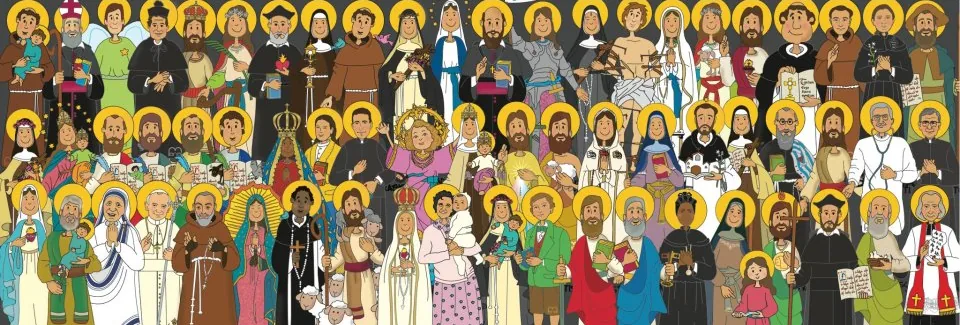

!(center)https://radialistas.net/wp-content/uploads/media/uploads/fotos_series/otro-dios/76g.jpg(alt_text)!

RACHEL We renew our transmission from outside the church of Saint … No, it’s better if we omit the identity of the place to avoid recriminations. Jesus Christ, who is here beside me, still seems surprised by what we saw inside the church, which is not very different from so many others, full of statues and images of saints. What do you think of all that, Jesus?

JESUS It’s idolatry. Adoring images is idolatry.

RACHEL Well, Catholics claim they don’t adore them, they venerate them.

JESUS Venerate? I’m not familiar with that word, but it seems to be the same thing. Instead of speaking to God, who dwells in their heart, they kneel down before a piece of wood.

RACHEL We have a call…. Yes, hello?

ANDRÉS Hello, this is Andrés Pérez Baltodano. I’m calling from Canada.

RACHEL Do you wish to offer an opinion, Mr Baltodano?

ANDRÉS I’d just like to say to Jesus Christ that the problem is not with the word, the verb “venerate”, but with something more substantial.

RACHEL And what is that?

ANDRÉS It’s the “substantial” income that the Catholic Church receives with this business of the saints.

RACHEL Don Andrés, could you explain yourself a little better?

ANDRÉS In case Jesus is not aware of it, the saint-making factory has still not been shut down.

RACHEL The saint-making factory?

ANDRÉS In that church you just entered you saw some old-time saints, saints from other centuries. But just during the pontificate of John Paul II there were manufactured, I mean, there were canonized no fewer than 464 new saints, more than in all the previous five centuries!

RACHEL And what do we need so many saints for? Don’t we have enough already?

ANDRÉS The thing is, the saints keep the people on their knees, and besides that, they increase the Vatican’s finances.

JESUS That “besides” is what I don’t understand.

ANDRÉS Making a saint is a complicated process, Jesus. You need witnesses, tribunals, experts, demonstrated miracles, examination of the corpse to see if it decayed or remained incorrupt. Pursuing the cause of a saint can take years and years.

RACHEL And that costs a lot of money, right?

ANDRÉS It’s very expensive, and that money goes straight to the Vatican vaults. Just think of this one detail of every hundred saints canonized in the course of history, only five were poor people. The immense majority were princes, kings, queens, bishops, abbesses, … Their friends and family paid a fortune for them to be made saints. Nowadays the saint-making factory is much more organized nobody reaches the altars without having some powerful institution behind them.

JESUS May I ask you a question, don Andrés?

ANDRÉS Of course, Jesus.

JESUS Why do they go through all that?

ANDRÉS The canonization process?

JESUS Yes, that process which is so costly.

ANDRÉS To show that the saint is in heaven, at God’s side.

JESUS But that’s looking for treasure where there isn’t any. The saints aren’t in heaven, they’re on earth!

RACHEL Now I’m the one who doesn’t understand.

JESUS The saints are here among us. They are people of flesh and blood. The women who spend their lives helping their children get ahead – those are the saints. The impoverished farmers who are laboring in their fields from before dawn – they’re saints. The good people who fight for justice, who place God and their neighbors above money – those are the real saints.

RACHEL But they always told us that the saints are people who die and then perform miracles from heaven.

JESUS No, the saints are still alive. And they perform miracles when they give us good example. My father Joseph was a saint, but not because of that little crown they put on the statue of him there in that church, but because he was just until the last day of his life.

RACHEL But … And if people who are still in the world are saints, what should we call the others, the ones who are already with God?

JESUS That … that’s something you should ask God.

RACHEL Many thanks to the friend who called from Canada. And thanks also to so many saints who are certainly part of our great audience here at Emisoras Latinas. From Jerusalem this is Rachel Perez reporting.

MUSIC

ANNOUNCER Another God is Possible. Exclusive interviews with Jesus Christ in his second coming to Earth. A production of María and José Ignacio López Vigil, with the support of the Syd Forum and Christian Aid.

*More information about this polemical topic…*

“They reign together with Christ”

The Catholic Church is the only Christian denomination that has a formal juridical and administrative mechanism for establishing that someone is a “saint”. The one who makes the final determination is the Pope. The purpose of “canonizing” someone (making him or her a saint) is to present the person to the faithful as an example and a model to follow.

In the earliest centuries the “saints” were venerated as such by popular acclaim, the “vox populi”. Later on, to avoid abuses, the bishops agreed that they would be the ones who decided which persons were to be declared “saints” in their respective dioceses. Starting in the year 1234 that power to name saints was reserved exclusively to the Pope. In 1588 Pope Sixtus V put the process in the hands of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, one of the many structures of the Vatican bureaucracy. In the 16th century the Council of Trent reaffirmed this doctrine: The saints, who reign together with Christ, present their own prayers for human beings before God. It is good and useful to beseech them in prayer in order to receive the support, aid and protection they can provide through their prayers and to receive, even more, God’s grace.

A long and costly process

The process for making a saint is long, costly and complicated. It begins when a bishop, a religious congregation or some other institution presents to the Vatican a report on the life of a person whom they wish to be declared a saint. The Vatican investigates the life, the virtues and the defects of the person, and it seeks the opinions of others. If after due examination it decides that there are no objections, then the person begins to be called “servant of God”. In order to pass to the second stage, that of being a “blessed”, the person is submitted to further investigation as regards his or her virtues, and there must be at least one miracle (generally, certified healings) attributed to him or her. Occasionally it is considered a miracle when the corpse of the candidate to sainthood has remained incorrupt, and this is given serious consideration by the Vatican. According to some studies, the Catholic Church has recognized 102 corpses as being preserved miraculously incorrupt.

After the beatification, the final step of the process is “canonization”, which occurs after another miracle has been certified by the Vatican tribunal – it is almost always the curing of some disease. That is when the Pope proclaims that the person is a “saint”. Canonization means that the person is “elevated to the altars”: the faithful can venerate and pray to him or her, a feast day is assigned in the calendar of liturgical celebrations, images and holy cards can be made of the saint, and his or her relics can be distributed to the faithful.

The cult of the saints

The exaggerated cult of the saints in the Catholic Church is evident in a great number of churches, which appear more like “Olympuses”, mountains of the gods, because of the proliferation of virgins, saints and even “Jesuses”. Such a style of veneration discloses archaic religious conceptions which predate Christianity.

The Babylonians, for example, had around five thousand gods and goddesses. They believed that those divinities were heroes who had lived on earth and worked wonders and that after death had passed to a higher existential plane, where they were able to continue acting on behalf of humans. Each day of the year was protected by one of those deities, and every situation in life required the assistance of one of them. Every group and organization had its special protector or patron. With some variations these ideas and practices appeared in all the religions of the ancient world, and they are very similar to the ones that can be seen in the Catholic cult of the saints. There are thousands of saints (five thousand in the official list), and they function as patrons of all kinds of places and all types of professions; they are advocates in the most dissimilar kinds of situations. It can therefore be stated that within Christian monotheism there survives a kind of ancient polytheism, which is especially evident in this deep-rooted veneration of the saints.

The Catholic cult of the saints results in dogmatic contradictions. In view of the veneration of the saints it may also be asked: Is this a type of cult of the dead or of spirits? Is it a form of spiritism? After all, those saints are all dead and buried, waiting the last times, the final judgment, and the promised resurrection. How then are we to invoke them? And if they are dead, how can they “reign with Christ” and “contemplate God”, such as is proclaimed when they are canonized? And how can they mediate and intercede before God, who is in a “place” different from where they are?

The costs of making a saint

It is not easy to calculate the finances needed to “manufacture” a saint, that is, to have the Catholic hierarchy in the Vatican officially declare that such and such a person is “with God”, is a “saint”, and therefore can be prayed to for miracles and favors – all that is what being a “saint” means in the Catholic world. There is not much information or much transparency about the real costs of these processes.

In this book The Princes of the Church, published in the 1980s, German historian Horst Herrmann states: The Vatican does not invest a single lira in any canonization. It requires payment for everything, from the first compilations of acts till the festive papal mass with which the process concludes (just renting Saint Peter’s Basilica costs ten thousand dollars). In his book Making Saints (1992), writer Kenneth Woodward calculates the total cost of a canonization at 250 thousand dollars minimum. Since the cost of living increases continually, the cost of “sainthood” does also. Writing a few years later, Charles Panati states in his Popular Dictionary of Religious Objects and Customs that the “approximate cost” of a canonization should be put at about a million dollars.

Naturally, Vatican finances are helped greatly by such “manufacturing” of saints. For those who want to have the founder of their religious congregation proclaimed a saint or for those who seek to promote the importance of somebody by having him or her declared a saint, it is just a matter of investment.

John Paul II: a historic record

During the 26 years of his pontificate, Pope John Paul II canonized more persons than were canonized by all the popes during the previous five centuries. John Paul added 482 new saints to the four thousand that already existed. He also beatified some 1338 persons, thus putting them on the road to “sainthood”. The “specialist in saints” who participated in our program actually mentioned a smaller figure of new saints: 464 – a few saints more or a few saints fewer, the number is still a record.

Andrés Pérez Baltodano is a Nicaraguan who is a professor of political science in Canada. He participates in our program because of his lucid critique of what he calls the “providentialist vision” of religion and the “resigned pragmatism” promoted by a Vatican-controlled church. He has also done research on the consequences of this religious culture for the Latin American political scene.

In one of his articles Baltodano writes: The posture of resigned pragmatism and the providentialist vision of power and history is reinforced more and more by the Vatican. The providentialism promoted nowadays by the Vatican is expressed, for example, in the scandalous number of saints that have been canonized by Pope John Paul II. The Vatican is making serious efforts to resacralize the world on the basis of providentialist ideas, since it canonizes only persons who “work miracles”, that is, persons who confirm the view that a providentialist God acts directly in human history. In order to maintain its power, the Church has unfortunately decided to resacralize the world and to reinstitutionalize providentialism. It has decided that its power will be easier to sustain through a renewal of providentialism, and this worldview, in a rather perverse way, coincides nicely with the workings of the global market.

The cult of the saints forms part of the “magic sense of life” that is part and parcel of the political culture of our Latin American countries. For most of our people natural phenomena and social and human events have a mysterious, impenetrable source: they are the product of extraordinary forces. In politics, this cultural trait is expressed in the tendency of people to have faith in the powers of whoever is the current political boss.

The saints live among us

To be holy or saintly means to make present in the world the Holy of Holies, God, the God of Jesus. It means making really present his goodness, his compassion, his justice. Being holy means being exemplary, being “like God”, revealing God’s presence in equitable human relations, in the “miracle” of sharing possessions, and becoming responsible for the inclusion of those who have been excluded. In the Church’s early tradition the “saints” were live, exemplary persons of flesh and blood who kept the project of Jesus alive within the Christian communities. The letters of Paul and Peter refer repeatedly to these “saints”. The cult of the saints, in which they are understood as intermediaries or “secretaries” standing between us and God, is something that came much later. It not only distorts the early understanding that the early Church had of the word “saint” but also warps the very image of God, reducing him to a sort of very busy monarch with a large team of servants at his beck and call.